MCNY Blog: New York Stories

Iconic photos of a changing city, and commentary on our Collections & Exhibitions from the crew at MCNY.org

Penn Station and the Rise of Historic Preservation

After reading Lauren Robinson’s fantastic blog post about the return of Mad Men, I found myself haunted by the destruction of the original Penn Station. And as I dug deeper, I discovered that this was a drama of almost mythic proportions; a classic tale of David and Goliath; big corporations against a rag-tag group of underdogs; and art versus profit.

But first, the backstory: the original Pennsylvania Station was designed by Charles F. McKim, of McKim, Mead & White fame, the preeminent East Coast architectural firm of the Gilded Age. McKim’s designs drew heavily on classical architecture like the Roman Baths of Caracalla and the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin that elevated the mere activity of entering and leaving the city into a momentous occasion.

Penn Station was opened on September 8th, 1910, and its sheer scale immediately evoked a sense of awe. At the time it was completed, it was the largest building ever built (with the qualifier of “at one time”), and boasted the biggest waiting room in history. With 150-foot ceilings and natural light streaming through an iron and glass roof — how could one not think that they were somewhere magical?

George P. Hall and Son. Interior of Pennsylvania Station. 1911. Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.5113.

Berenice Abbott (1898-1991). Pennsylvania Station. 1936. Museum of the City of New York. 43.131.1.216.

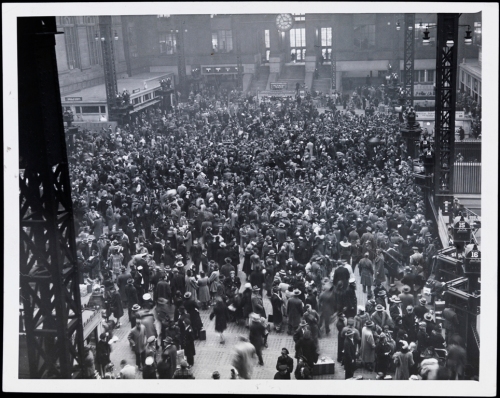

Wide World Photos, Inc. Crowds in Pennsylvania Station. ca. 1920. Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.5088.

Yet only 50 years after it was opened, Penn Station was in trouble. The owners of the station, Pennsylvania Railroad, were broke. The station was falling into disrepair. Airplanes and automobiles had begun to eclipse rail travel. With all this, the nine-acre lot between 7th and 8th Avenues from 31st to 33rd Street was just far too valuable not to sell. Even the architecture had gone out of style. The opulence and grandeur that were so popular in the Gilded Age were seen as an ungainly relic compared to the modern architecture of the 1960s.

At the same time, Madison Square Garden was outgrowing its location on 8th Avenue and 50th Street and its owners were eying possible building sites for a new, completely modernized sports arena. Suddenly there appeared an answer for both Pennsylvania Railroad’s financial problems and the continuation of Madison Square Garden. On July 25, 1961, the New York Times published the first mention of the relocation of Madison Square Garden to the site of Penn Station. What’s intriguing about this article is that the developers meant to keep the original station waiting room as part of the new facility. Two days later it became apparent that this was not going to happen, and on July 27, 1961 the front page of the New York Times ran the headline “’62 Start is Set for New Garden — Penn Station to Be Razed to Street Level in Project.” The planned $75 million complex included a hotel and a 34-story office building, along with a 25,000 seat arena and a smaller 4,000 seat arena, which the article described as “a huge, sagging pancake.” But, Irving Felt, the president of the company that owned Madison Square Garden, believed “that the gain from the new buildings and sports center would more than offset any aesthetic loss.”

This galvanized a group of five twenty-something architects calling themselves the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York, shortened to AGBANY, to organize a public protest against the demolition on August 21, 1962. From 5 to 7 P.M, they picketed in front of Penn Station carrying signs reading “Shame” and “Don’t Amputate — Renovate.” Reports vary that at least 150 people participated and soon organizations like the Municipal Arts Council joined the fight to save Penn Station. For the next year, the battle continued. Larger protests from city residents, however, didn’t come until it was too late.

On October 28, 1963 at 9 A.M., as a light rain fell and picketers wearing black armbands watched silently, electric jackhammers began to destroy Penn Station. For the next three years, Penn Station was slowly demolished. The destruction was brutal and total; the station’s monumental ornamentation – 16-ton decorative eagles and the 84 Doric columns that made up the Seventh Avenue facade – were dumped unceremoniously into the marshlands of Secaucus, New Jersey.

Aaron Rose. The demolition of Pennsylvania Station, 1964-1965. Museum of the City of New York. 01.30.82

Aaron Rose. The demolition of Pennsylvania Station, 1964-1965. Museum of the City of New York. 01.30.2

Aaron Rose. The demolition of Pennsylvania Station, 1964-1965. Museum of the City of New York. 01.30.79.

Aaron Rose. The demolition of Pennsylvania Station, 1964-1965. Museum of the City of New York. 01.30.95.

Aaron Rose. The demolition of Pennsylvania Station, 1964-1965. Museum of the City of New York. 01.30.117.

As a direct result, on April 15, 1965, Mayor Robert Wagner signed the Landmark Law, which created the Landmarks Preservation Commission. For the first time there was an agency with government power to designate and even save historical buildings and neighborhoods. The legal ramification didn’t end there though. A year later, after growing countrywide preservation efforts, the National Historic Preservation Act was enacted, ensuring that other cities wouldn’t also have to lose a landmark to realize the importance of its preservation.

Below are some of the strikingly emotional reactions to the destruction of Penn Station from the New York Times:

“Farewell to Penn Station” on October 30, 1963 “Until the first blow fell, no one was convinced that Penn Station really would be demolished, or that New York would permit this monumental act of vandalism against one of the largest and finest landmarks of its age of Roman elegance. Any city gets what it admires, will pay for, and, ultimately, deserves. Even when we had Penn Station, we couldn’t afford to keep it clean. We want and deserve tin-can architecture in a tinhorn culture. And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed”

Ada Louise Huxtable wrote the following on July 16, 1966: “Pennsylvania Station succumbed to progress this week at the age of 56, after a lingering decline. The building’s one remaining facade was shorn of eagles and ornament yesterday, preparatory to leveling the last wall. It went not with a bang, or a whimper, but to the rustle of real estate stock shares. The passing of Penn Station is more than the end of a landmark. It makes the priority of real estate values over preservation conclusively clear. It confirms the demise of an age of opulent elegance, of conspicuous, magnificent spaces, rich and enduring materials, the monumental civic gesture, and extravagant expenditure for esthetic ends.”

Vincent Scully, Jr., as quoted in the New York Times on February 12, 2012 about the differences in the Penn Station: “One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat.”

For a detailed study of the demolition of Penn Station, check out The Fall and Rise of Pennsylvania Station. Changing Attitudes Toward Historic Preservation in New York City by Eric J. Plosky, found here.

During the month of May, we’ll be posting more entries on historic preservation in the city. The Museum of the City of New York is competing for a $250,000 grant from Partners in Preservation, a joint program sponsored by American Express and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The winner is determined by popular vote, and individuals may vote once a day through May 21st. Please help us by going to http://www.helpmcny.com/ and voting today.

Very moving post. How sad that one generation’s treasure is another generation’s trash… especially when there’s money to made.

Susannah: Great piece. By the way AGABNY five architects included Eliot Willensky, now deceased, the great co-author of the AIA Guide to NYC, and also Peter Samton and Jordan Gruzen, partners in the Gruzen Samton architectural firm. Patricia

So much of what NYU has done in and to the Village will, I believe, someday be seen in the same light of regret. The destruction (except for a token element) of the Edgar Alan Poe House, The Provincetown Playhouse, the ruin of many splendid interiors of houses on Washington Sq. North and in the East Village, all of it should’ve been stopped. That fact that it was done by an institution of allegedly higher learning makes it all the more obscene.

The destruction of Penn Station is one of those delicious historical events that is both a tragedy and a triumph. It was terrible to lose that building, but because we lost it we saved hundreds of others.

Pingback: The original Penn Station – New York City « History Never Dies

Pingback: The Treasures of Grand Central at 100 | Mindful Walker

Pingback: A Century of Grand Central Terminal | mcnyblog

Pingback: Modernisation in favour of tourism | Modernisation or Conservation?

Pingback: If a Building is Demolished and No One Cares, Did it Even Exist? | raina regan

Pingback: The Rise and Fall of Penn Station, Chapter1 - Saving Arkansas Places – Saving Arkansas Places

Pingback: Pennsylvania Station: Its Glory and Its Demise | Mindful Walker

Pingback: The History of NYC’s Landmarks Law and Modern Day Preservation Movements — UrbanCincy

Pingback: The Crown Jewel of Brooklyn – Prospect Park | MCNY Blog: New York Stories

Pingback: ‘One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat’ — See beautiful pictures of New York’s old Penn Station before it was torn down | News World

Pingback: 7 iconic buildings across the US that no longer exist — and what’s in their place today – CapitolZero

Pingback: 7 iconic buildings across the US that no longer exist — and what’s in their place today – Helen Smith's Blog