MCNY Blog: New York Stories

Iconic photos of a changing city, and commentary on our Collections & Exhibitions from the crew at MCNY.org

The “Forgotten” Father of Greater New York: Andrew Haswell Green

November 13, 1903. An 83 year old man leaves his office at 214 Broadway and gets on the Fourth Avenue street car by City Hall to join his nieces for lunch at his home. At 38th Street and Park Avenue, he disembarks the car and walks toward his house at 91 Park Avenue, a mere three houses away from the station. At his front gate, a man rushes at him, accusing the older man of turning a woman’s affection against him. (For a highly dramatic take on the confrontation read the opening of this Daily News article.) A passer-by hears the older man shout, “Who are you anyway? I don’t know you! Get away from me!” Five shots are fired, and the older man falls dead, right inside of the gate to his property. The shooter stands over the body with his revolver, his shoulders heaving, but his feet rooted in place. When the police arrive, he finally turns and blurts out: “He deserved it, —- him! He forced me to do it!” (New York Times.)

So begins the strange tale of the life — and death — of Andrew Haswell Green. Never heard of him? That’s completely understandable. Despite doing so much for New York City, and helping make it into the city we know today, his name faded into obscurity. However, it just takes a cursory glance around the five boroughs to see that the legacy of A.H. Green never faded at all. In fact, it thrives: Consolidation of the five boroughs? Green did that. Central Park? A.H. Green. The American Museum of Natural History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Bronx Zoo, Washington Bridge in Harlem, and New York Public Library? They all owe their existence to this one man. Green could perhaps be compared to the other great master builder of New York City, Robert Moses, just without the controversy. He is also one of the first preservationists, and was praised by nearly everyone for his single-minded, constant effort to improve his adopted city.

Andrew Haswell Green was born in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1820. He moved to New York City at the age of 15, where he worked as an errand boy, before eventually making his way through law school to became a partner in Samuel J. Tilden’s law firm. Perhaps inspired by Tilden, it was during this time that he began his lifelong quest for the betterment of New York City with a position on the Board of Education in 1855; three years later he was the president of the Board. He had found his passion.

Public parks and green spaces were not part of the 19th century idea of a city. Due to the rapidly growing population of Manhattan, however, city officials began looking for an area in the wilderness above 42nd Street to locate a park, and Green was elected to the Board formed to oversee its creation. When the landscape architects Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted presented their plans for the urban oasis, Green was so taken and inspired by their proposal that he had the board create the position of comptroller for him, ensuring his close involvement. As with many public building projects, the park was already over budget and behind schedule. But in short order, Green managed the finances and even stepped into controlling the daily operations of the park building, from the construction schedule to the deciding of materials — much to the dismay of Vaux and Olmsted. Green drove the architects crazy with his own ideas about everything in the park, while also keeping them on a tight financial leash. Despite their personal difficulties, the three men managed to fund and create one of the world’s most beautiful and recognizable urban open spaces: Central Park.

Sarony, Major & Knapp Lith. Map showing the original Topography of the site of Central Park with a Diagram of Roads and Walks now under construction. Museum of the City of New York. 50.358.60

In 1871, the Tweed Ring, the corrupt political organization that controlled the city’s finances, was ousted and its leader, Boss Tweed, thrown in jail by Green’s old friend and mentor Samuel J. Tilden. The city reeled from the sudden loss of leadership, and was nearly left in financial ruin. Andrew Haswell Green came to the rescue again. He was elected Acting-Comptroller and went to work balancing the budget and doing whatever else it took: things were so bad, an apocryphal story tells of him paying the police force out of his own pocket. He stayed on as the city’s Comptroller for the next five years, leaving the city’s coffers in much better shape than he found them.

Green was discussed as a candidate in nearly every mayoral election from 1876 to 1896. The closest he came to actually running was in 1876 when the Independent Citizens Committee nominated him on a Reform Ticket. For once, he was unsuccessful.

Reform Ticket, Independent Citizen’s Committee, Mayor, Andrew H. Green. 1875-1876. Museum of the City of New York. 2011.5.13.

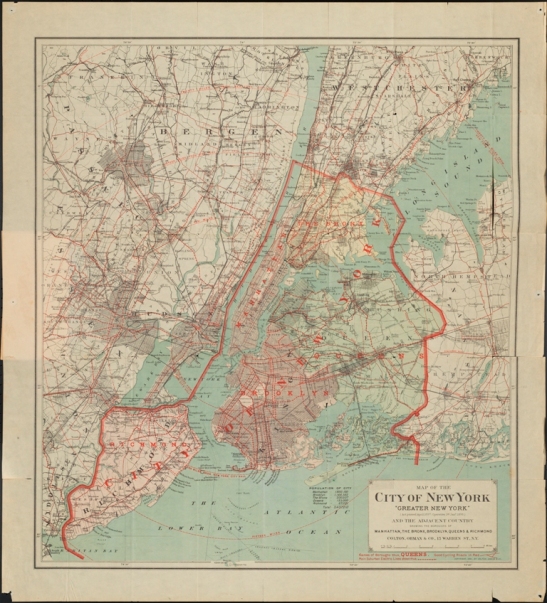

However amazing all of these contributions are, they are overshadowed by what the press dubbed “Green’s hobby.” In a word: consolidation. Green wanted to see all the competing towns, villages, and settlements in Manhattan, Richmond, Kings, The Bronx, and Queens counties under one government. As early at 1868 he was the sole voice championing consolidation. For over 20 years he lobbied hard for this, despite bitter opposition from entire cities (namely Brooklyn) and various political hurdles. He helped draft the Consolidation Law in 1895 which was passed in 1897. On January 1, 1898 Greater New York was a reality.

One explanation for why Green’s legacy faded into obscurity, other than just New York being fickle, might be related to his shocking death. The story at the time, was his murderer, Cornelius M. Williams, was in love with a woman who had moved her affections on to an older gentleman with the last name of Green. Williams was so jealous that he consulted the city directory and found the first Green listed, Andrew H. Green, and laid in wait for an opportunity to show his displeasure. That opportunity presented itself on November 3, 1903 when he murdered a man for having a common last name. However, the reality is just as coincidence filled and involves a man named John R. Platt, read all the salacious details in this New York Times article.

Right after Green’s death, there was a plan to name a road running along the edge of Manhattan after him, but plans floundered and for years, the only public monument dedicated to Green was a bench in a remote area of Central Park. In 2011, thanks to the tireless efforts of Manhattan Borough Historian Michael Miscione, Andrew Haswell Green Park on the bank of the East River between 59th and 63rd Streets opened to the public. Hopefully this will be the first step in remembering the forgotten father of Greater New York.

great read, thank you.

I have written a book about this murder and its consequences .Can you contact me?

Fascinating. Thank you for enlightening us about this man with the vision that shaped NYC.

This is one of the strangest, and most fascinating, New York stories I’ve ever heard. And I’ve heard a few

Great read! So nice to see info about Green. I recently published a biography about this amazing civic leader. “New York’s Father is Murdered! The Life and Death of Andrew Haswell Green.”

Pingback: Conservation of the J. Clarence Davies Map Collection | mcnyblog

It’s amazing what one man can do. His name should be all over Manhattan and the boroughs.

Your description of Green’s murder doesn’t fit with the NYT article. There was mistaken identity, but the man Green was mistaken for was named Platt. Read the article for the rest…

My forthcoming book, “Metropolitan: Hannah Elias and the Murder of the Man who Invented New York,” argues that the DA, William Travers Jerome, engineered a cover-up surrounding the murder to protect wealthy white clients of the African American courtesan, Hannah Elias. Williams, the killer, was not insane nor did he mistakenly identify his victim; after a sham sanity hearing, the DA had him committed without a trial to prevent his appearance in court. The DA feared that William’s testimony would require the calling of Elias as a witness and that she would reveal a list of the names of her wealthy white clients. Platt’s suit later that year complicated his plan.

Steve,

Thank you so much for pointing out that I was unclear in that paragraph. I’ve updated it to include John R. Platt’s involvement.

Pingback: New York Today: Changing Colors | Sellcop

Pingback: #New York Today: Changing Colors - the press

Reblogged this on HowCitiesWork.

Pingback: Sabrina’s Pool, Central Park – Hidden Waters blog

Pingback: The Loch, Central Park – Hidden Waters blog

Thank you for this very interesting article. I love researching about our, Forgotten Fathers, and people. It gave me a wee bit of a chance to see into his life for a little while. I love learning about the unknown people. Thanks again.

Pingback: The Pool, Manhattan – Hidden Waters blog